Cassidy’s Circus: Confessions and the NYC Underground Literary Scene

The New Wei is proud to introduce our second article on dynamic, boundary-pushing artists among the post-pandemic NYC indie arts scene. Our first article, "The Light Side of the Moon: Scarlett Taylor's Veil", focused on a 23 year old musical auteur who created her own themes and incorporated them in her 13 song debut album, releasing the songs each month for over a year, inspired by a camaraderie of fellow budding musicians.

This second article, "Cassidy's Circus: Confessions and the NYC Underground Literary Scene," investigates a community of underground authors led by writer/actress Cassidy Grady, who, teaming up with her friend, showgirl Angel Tramp, created and still runs the most innovative reading series in NYC: Confessions. The result has been a renaissance of bizarre tales created from confessional prompts told to an ever-widening crowd of listeners. Can this lead to more bold, provocative literary content and form across the board? Well, it's already inspired one copycat reading series, so we shall see!

The most dynamic reading series in New York City is taking place on Sunday nights. About every two weeks, around 200 people stream into Sovereign House, a basement-level space in the Lower East Side micro-neighborhood Dimes Square that hosts many arts events.

But that Sunday night is special. People come ritualistically, almost sacrilegiously, to first “confess” their sins in a dark telephone booth, then listen to one reader after another recite their boundary-pushing and bizarre autofictive tales using those very confessions as prompts.

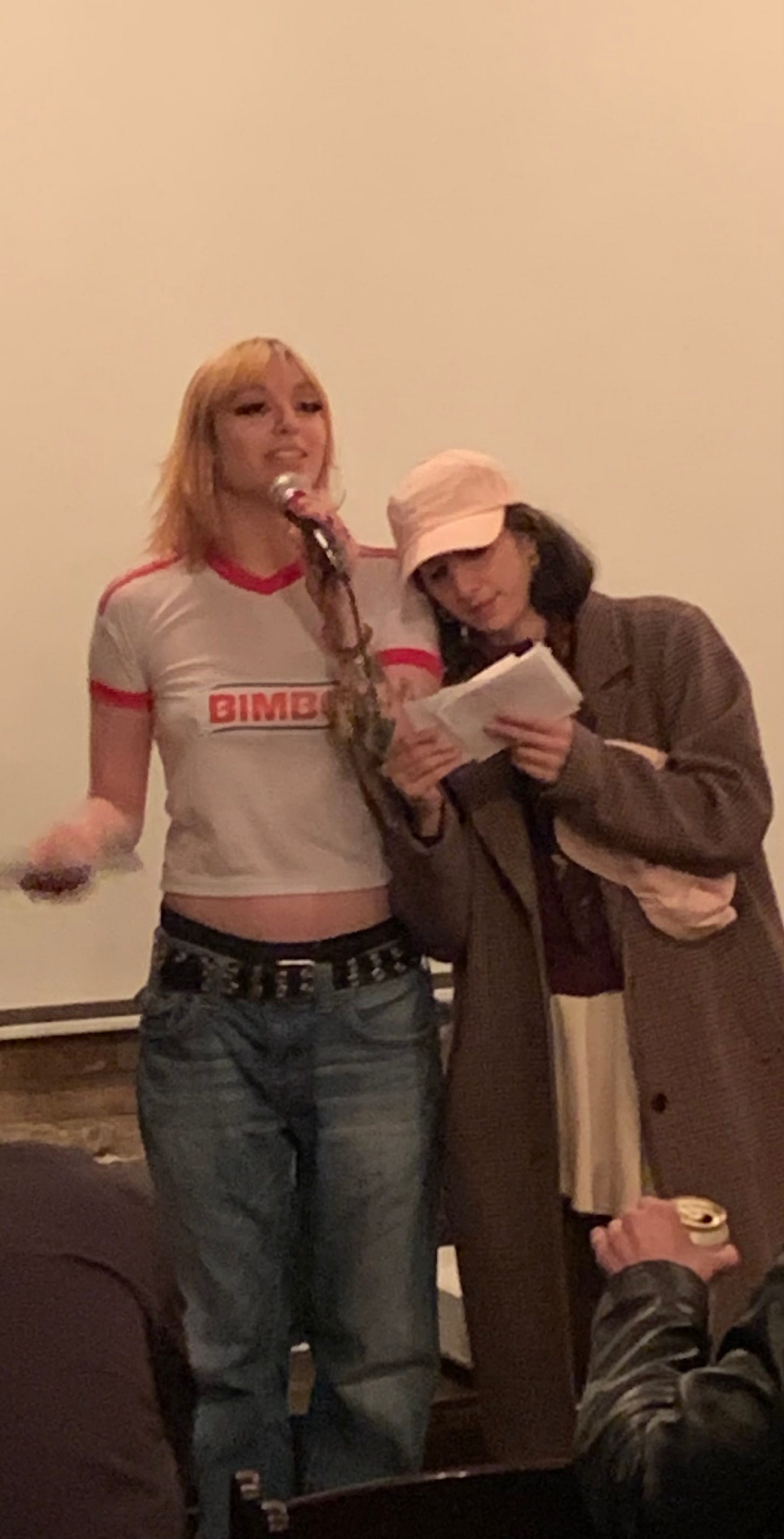

This innovative series, started in October 2023 and taking place about every two weeks, is the brainchild of two “angels” — Cassidy Angel Grady, a seasoned veteran of NYC underground theater, and Angel Tramp, a showgirl by trade and recent literary convert. Together they have created a mission and solved a quandary — how to “Make Readings Great Again,” as stated on a fancy pink hat given away as merch.

As both Cassidy and Angel told me, most literary readings are boring and one note: brief clippings from the work of invited authors, usually capped by the “famous” author. Confessions, with stories based on prompts written by anonymous individuals, is generative, and the order of readers is chosen randomly — no one is singled out as being special.

Although the readers are often published authors from within the underground literary world, there are no introductions, bios or notes about the author’s previous work. The authors come up and read from their phones the tale they created from the confession they chose. There’s no length or time limit, which is nearly unheard of in the literary world. This gives the series not only a democratic aura and sense of freedom but surprisingly creates its own integrative framework.

Apparently, Confessions was created by the two Angels while they partied at a club late one night (the decadent details were withheld from me). Cassidy is also a “club girl” who makes her living by hosting at high-end clubs in the Lower East Side and Midtown, particularly Paul’s Baby Grand; more recently, she created her own cryptocurrency, called E-girl coin. Angel Tramp works Wednesday through Sunday when her agency can find her work, whereas Cassidy usually works twice a week.

The two Angels were college roommates at Marymount Manhattan College in the Upper East Side. Cassidy is an Italian Catholic from New Castle, Pennsylvania, outside Pittsburgh, but she has been coming to New York City as a practicing ballerina since she was a little girl. Angel is an Irish Catholic originally from Saratoga Springs, NY. Both are subversive artists, challenging people’s inhibitions at every turn.

Graduating during the pandemic, Cassidy began acting in underground theater, often in private apartments, most notably Matthew Gasda’s play Dimes Square, which satirizes the post-pandemic alt-lit crowd, many of whom are children of famous writers and artists. Grady joked about being a “nepo baby” because her mother was a ballerina — that doesn’t seem like an exact correlation into the literary sphere, however. Gasda was her boyfriend at the time of Dimes Square’s initial run, but they have since broken up.

Subsequently, Cassidy has produced her own plays: Fire Wars, a relationship drama set in a cabin in the woods, and A Thump, A Thud, A Roar, a tragic farce set in the Circus. One was performed at the now defunct Beckett’s Salon and the other at Hancock in Bedford Stuyvesant.

These two-act plays feature reversals of situation and play within relationships during adulterous entanglements. Innovative in content and form, A Thump, A Thud, A Roar features the same actors playing different characters in its second act — even the characters change as we see a reflection from different time periods in their lives. Both plays push the boundaries of what we expect from their respective settings as well.

More recently, Cassidy is starring, as an actress, in Jonah Howell’s play Lillita and the Tramp about Charlie Chaplin’s second wife, Lillita Grey, who worked a divorce judgment against the silent film star about a century ago for $825,000.

Cassidy also writes provocative fiction — she published a story “Hi I’m Holly” in Forever Mag about a girl who wants to be trafficked despite her preferred abuser’s indifference; “Camille’s Tale” in Man’s World, an excerpt from a larger novel that integrates and reworks classic fairy tales like Snow White and Sleeping Beauty; and “In Retrospect I Realize” in Expat, which is a “confession” from daughter to mother in letter format. Her Substack blog “In the Middle, Somewhat Decimated” includes fiction, works of art and literary theory, musings on religion and cryptocurrency, as well as accounts of her social adventures.

Angel Tramp is a showgirl who was discovered by a model agency promoter while dancing at Le Bain in the Meatpacking District. She performs both scripted shows and improvised acts in extravagant costumes at various high-end clubs in Manhattan. One of her favorite ruses is coming up to a seated group, crouching down as a gargoyle and announcing herself in a matter-of-fact tone. Like burlesque, her goal is to reduce people’s inhibitions and get them out of their comfort zone.

While she has less experience in the literary world than Cassidy, they share a love for libertinism and perversity, making them perfect foils — Cassidy says they are essentially ying-yang, exchanging literary and club hats.

This libertine streak translates itself not only to the content of Confessions but also to its enactment: at the end of one of Confessions, Cassidy reminded the crowd that the night was endless (after the readings, the afterparty can last all night) and recommended they “kiss someone.” While she has a boyfriend, who she lives with, she often posts about being attracted to many men, and she fronts an e-girl aesthetic, which is characterized, among other things, by women who crave male attention. Her favorite writer is Anais Nin, who was notorious for her affairs, and her friend dubbed her “the Anais Nin of the greater Dimes Square area.” Smoking and vaping are common to this crowd, as are drug and alcohol use. And while that is typical of any literary scene, one clue to its genesis may lie in the jolted isolation this generation experienced during the Covid pandemic.

While Cassidy bore the isolation by acting in underground plays, Angel Tramp recalled selling vintage clothing online. The lifting of the pandemic restrictions finally led her to go out and find her way. Both Angels were able to spread their wings during a time when most people were still cowering under fear and masks. The result seems to be a dedication to decadence and a distrust of conventional politics.

The venue that hosts Confessions, Sovereign House, holds nearly nightly events. During my first interview with Cassidy Grady, she told me she was going to a fundraiser for Douglass Mackey, who posted memes in 2016 suggesting people could vote for Hillary Clinton via text with actual links to do so. The Justice Department claimed this was election interference that targeted black and Hispanic voters; he was convicted by a federal jury and sentenced to 7 months in prison.

His supporters claim this was satire and that it is a dangerous precedent to prosecute and jail a man for exercising his First Amendment Rights. Sovereign House hosts many events to promote provocative and subversive artists, tending to have a bend towards libertarian and anti-woke politics.

The ideological thrust behind Confessions is partially based on lapsed Catholicism, Original Sin, and the breaking of its chains to create subversive experience, but it also relies on the traditions of autofiction, metafiction and microcelebrity. Especially in the world of social media “telephone,” it questions the very nature of truth and authenticity in a time when gossip, innuendo and accusations often seem more important than objective truth.

The first step in the literary process is the writing of the confession. Like Clark Kent, a person enters a telephone booth in a darkened corner of a lively space, yet suddenly, confronted with an uncomfortable seat, pen and paper, they need to write a confession as if they are a guilty individual facing a priest. What are your deepest and darkest secrets? Please confess them.

Being confronted with this dilemma, and perhaps knowing that it may become a prompt for a fictional piece, what is the likelihood that individual will write a confession that is true? One person confessed to having sex with Saddam Hussein, another with sleeping with her half-brother in the basement of her family home after discovering her father had a second family, and a third claimed to hunt predators and kill four rapists. While changing things up at one Confessions, the Angels read a particular prompt and asked who had written it: it ended up being a girl who admitted to being fondled by a priest and enjoying it (at least, when a better-looking priest came along and did the same). Her reward was the “Make Readings Great Again” hat mentioned earlier.

The confessions gathered from the previous event are compiled on a rolling word document that is typed up by Angel Tramp. The confessions are then sent to the prospective readers, who are normally chosen by Cassidy Grady due to her enormous social reach among the alt-lit crowd. The writers choose a prompt, then write their Confessions piece based on it. The writer has the option of choosing when, and if, to reveal the actual confessional prompt. In some cases, it is not revealed at all.

I interviewed two Confessions readers to get their take on the series. Kathy Joyce is a prolific Substack writer who primarily writes about her personal experiences with drug use, rape, suicidal thoughts, agoraphobia and molestation. She is the former girlfriend of Caveh Zahedi, a filmmaker known for having people play themselves for a “documentary” effect. She sometimes writes on her Substack about their on-again, off-again relationship.

When I first met Kathy at Confessions, she claimed to be in a depressive, cyclical writing rut, so I was surprised when I encountered her enormous productivity on Substack. But she did admit to parodying herself during her Confessions reading. In fact, she chose her own prompt confessing to having been molested by her stepfather when she was 10–11 years old.

She started off the reading by claiming she did not choose her own confession as a prompt, but she then talks about the typical things she writes about in her Substack which includes getting molested 10,000 times by her Guatemalan stepfather when she was 10–11 years old. She also talks about her obsessions with race (she bitterly claims this molestation made her an honorary Latina; she also talks about how often she’s mistaken being Jewish, even though is a former Catholic who is now a Christian). The title of the piece is “Fucked and Fucked and Fucked”: this is a reference to a story she was told about a crazy person at an Apple Store who continuously yelled about how his Iphone was fucked. She cleverly uses this scenario to comment on her own obsessions with sex and rape, and at the end, she even uses the Confessions booth as the setting for a potential sexual encounter.

The piece also documents her experiences frequenting Sovereign House and engaging with the Dimes Square community, which also is a major focus of her Substack (Detective Kathy, in fact, interviewed Mike Crumplar after the infamous Dasha-slapping incident). There’s a sense in her reading, as there are in other Confessions readings, that she is speaking to people who read her Substack and are familiar with her.

Angel Tramp said that one of the purposes of Confessions to create a community where people can come every Sunday to the same reading series and see people they know, like in a church. Considering there are often 200 people registered for the event and that the room is usually packed for these readings, it seems to be a somewhat false assumption that everyone will know each other. In fact, at one reading in April 2024, Cassidy asked how many people there were new to Confessions, and more than half the room raised its hand.

Still, the community involved with Confessions seems more integrated than with other reading series. The Dimes Square literary crowd, for lack of a better term, have succeeded in promoting their community by mentioning each other in memes and social media posts, especially on Instagram and Substack. The insularity inherent in Kathy Joyce’s approach to her Confessions piece demonstrates the somewhat incestuous nature of the series. But it also shows how meta it is, how willing it is to refer to and criticize its own aesthetic, community and procedures.

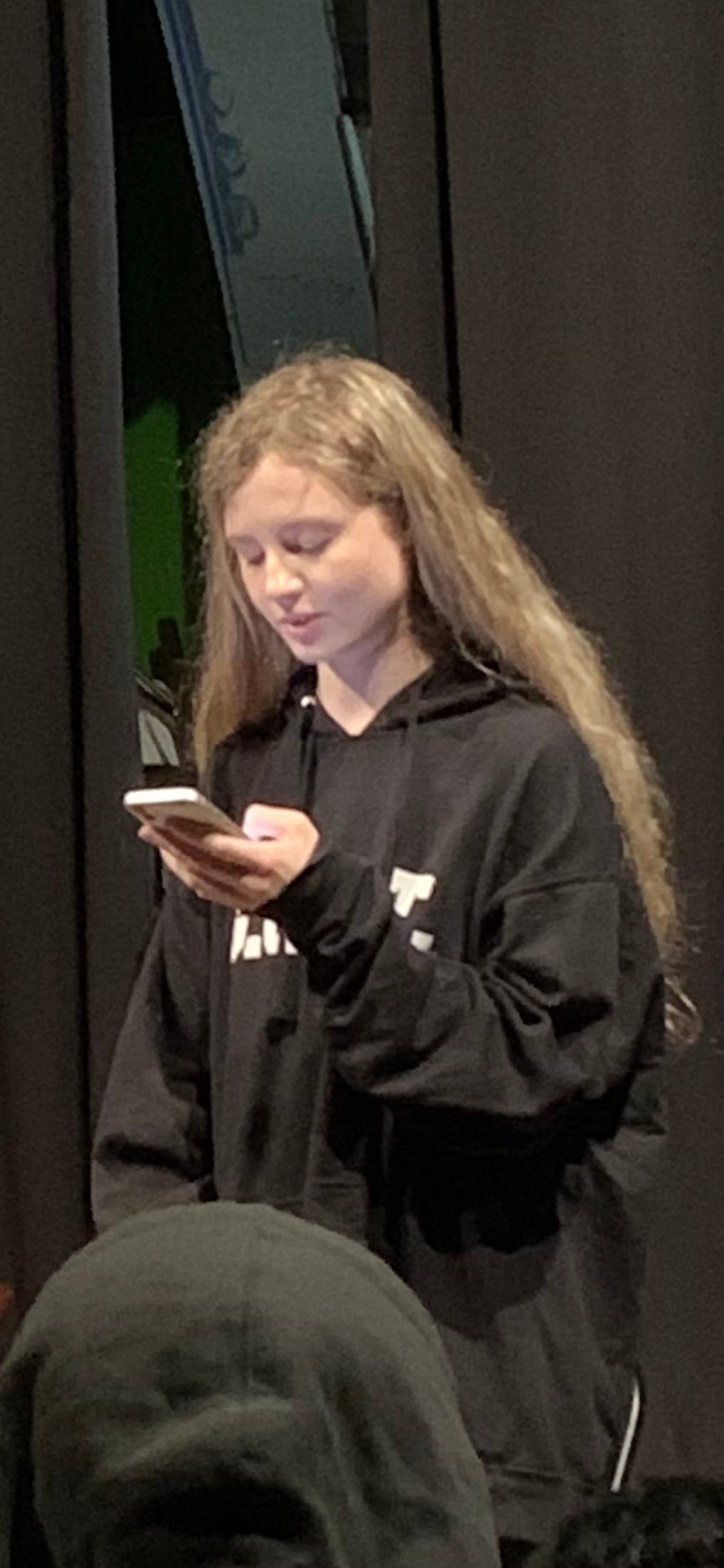

The other writer I interviewed was Adeline Swartzendruber. A current undergraduate in her junior year at Sarah Lawrence College, at only 20 years old she is on the younger side of the spectrum of this group of friends. She has produced less total material as a result (her Substack is bare), yet her piece expertly addressed the nature of Confessions itself.

Titled “I Got Lobotomized at the American Girl Doll Hospital,” and based on the prompt: “I am too forgiving to loved ones I’d kill for, but I foolishly hope and trust they love me back,” she begins: “That’s not a real confession. A confession is something you’re supposed to be ashamed of.” She then imagines the writing of the confession itself: “But this what I write on the blank piece of paper, drunk and dimly aware of a line forming outside. Everybody is armed with their wildest lie. Because this is a game of telephone disguised as a confession…”

However, unlike Kathy’s piece, Adeline did not write the confessional prompt, nor did she ever sit in the telephone booth to write a confession. In fact, the piece is totally fictional, even as it feels real, and continuously analyzes the ways that we discern and critique ourselves today privately, even as our public personas are at the mercy of an unforgivingly judging, often online, public.

From obsessively viewing her own Instagram (which, she claims, is triggered by the Confessions exercise) and progressively aging through Snapchat, to examining her life through “funhouse mirrors,” the piece imagines the Confessions writer (who has ostensibly written this bland confession) as she goes through the frustration of analyzing herself when that’s all most people do these days anyway. It plays with what “autofiction” is supposed to be, especially as a female (anorexia; bulimia; getting institutionalized and coming out with a new head and nice curls). The work uses Confessions to self-referentially critique introspection in our current times.

There are many other memorable works: Jonah Howell’s “Kelissa’s Education” which is based on a confession that is more of a question: “My confession is I’m curious about the satisfaction we get from viewing primal acts yet they are considered taboo.” From this prompt, Jonah made up a diary of a young woman named Kelissa, claiming it was found in a library in Louisiana in 2017, titled “My Education.” In it she describes how her father, a veterinarian, taught her about sex by demonstrating how he copulates with his favorite mistress: a sheep. The piece has the tone of outraged moralism (apparently, the father was run out of town “pitchforks and torches” by the townspeople once they learned of his deeds), claiming that Jesus was the “ultimate master of laughter and of restraint.”

Other pieces focus on rape via roofies, and babysitters fucking their bosses. One work by Cassidy Grady herself, “Odette Aurelia Clayton-Johnson,” is based on the confession: “I want everyone to come clean about their fetishes. When I was a teenager…I wanted to be a baby…and maybe I still want that now???”

The story describes a woman who is obsessed with wearing diapers. She is well-educated — her fantasies start in high school while taking her AP exams, and she implements them in college while attending Yale, fooling her boyfriend into thinking she has a bladder-control problem. Eventually, she has a child, who she admits she is jealous of due to her ability to wear said diapers. When her husband confronts her over taking care of her elderly father, she steals her baby’s diapers and wears them, being the same size — her husband mistakenly believes that she loves the daughter more than him.

Once again, this is a boundary-pushing piece exploring a perversion based not on a confession as much as a dare. Dares lead to greater dares, confessions prompt other confessions, stories weave into other stories, continuing the tag of “telephone.” Whether they are masturbatory or not seems rather besides the point, as one could easily say that all stories are masturbatory until they are received by the reader — then by nature they are congruous.

In the typical literary fiction reading, a group of authors read from their work, published or unpublished, and there usually is a featured writer — often the allegedly bigger dog. The works can be based on personal experiences or on invented characters, preferably based on research or extrapolation. The only difference with Confessions readings are the prompts, written randomly by others, and the lack of writer hierarchy.

The prompts play with the meaning of what a confession is — is it the revelation of something society considers taboo, and if so, is the subject so taboo that only fiction can reveal it? Is this the essential role of fiction as opposed to non-fiction — that the former can reveal what the latter cannot due to social restrictions? And who do we mean when we say society — the law, certain influential people, the “woke” mob that controls much of academia and punishes those who dare to bend or scribble outside its lines, or the conservative religious cavalry that behaves essentially the same way?

The lack of hierarchy is important to note at a time when promoting DEI is the rage, and yet, simultaneously, we have a nearly totally controlled and consolidated literary world (in fact, the recent firing of Lisa Lucas and others might mean DEI has been abandoned by major publishers anyway. Plus, independent publishers are in trouble, as evidenced by the fall of Small Press Distribution among other events). Diversity, Equity and Inclusion are all worthy goals, but do we truly have any diverse, subversive or provocative works being disseminated that aren’t self-published?

After all, to even be eligible for major literary awards, you need to be published by a “Big Five” major publisher (even though the vast majority of literary writers are self-published or published through indie presses). To be published by a major publisher, you need an agent who can sell the project. To get an agent, you need to write something that is sellable, and caters to the market. To cater to the market, you cannot be provocative, for the market likes what it has always liked — happy white grandmothers in book clubs.

The result is a safe literary work can get published, sold, read. By nature, the work cannot provoke or subvert. It cannot push boundaries. But it can win awards. And that can lead the writer to be part of the pantheon of great contemporary writers. Except by nature, they can’t produce something great by being safe. So, the cycle of mediocrity continues.

In a strange way, it is this hierarchy itself that promotes the bland content that sells today (and has for many, many years). Therefore, can the democratic framework promoted by a reading series like Confessions lead to bolder content and form across the board?

It also seems supremely ironic that many of these writers have self-reported being called “fascists” when this reading series, at least, is almost supremely democratic — the confessions are freely given, the prompts are chosen rather than forced, the works are created under zero rules or time constraints, and freely read to anyone who wants to attend.

I was offered to read, and I had no previous connections to this group, so there can’t be much restriction on that either. And while I was one of the only People of Color at the first Confessions I attended, at subsequent events I did notice that the crowd was ethnically diverse, perhaps somewhat allaying the fear that this is simply a “white” crowd. That said, I have experienced some hostility for wanting to write this article at all, but that may be a general fear of journalists digging into people’s lives.

I suppose the main question behind Confessions is whether the generation involved in it can not only Make Readings Great Again, but whether they can Make Literature Great Again. Certainly, the allusion to Donald Trump is unfortunate, but that doesn’t make the artistic mission any less important. Considering the mediocre and bland slop being produced by the Big Five publishers as “literary” and “multicultural” fiction, many of whom, somehow, go onto win Pulitzer Prizes and other major awards, one must consider whether the writers of Confessions, most of whom are in their 20s, can make a difference in this sorry state of affairs. That they are not seasoned veterans of MFA programs or “accepted” into the current elite is likely a positive. Can they break the chains of the obscurity designed for them and create great works and become great writers anyway?

Only time will tell, but I, for one, am willing to help them along.

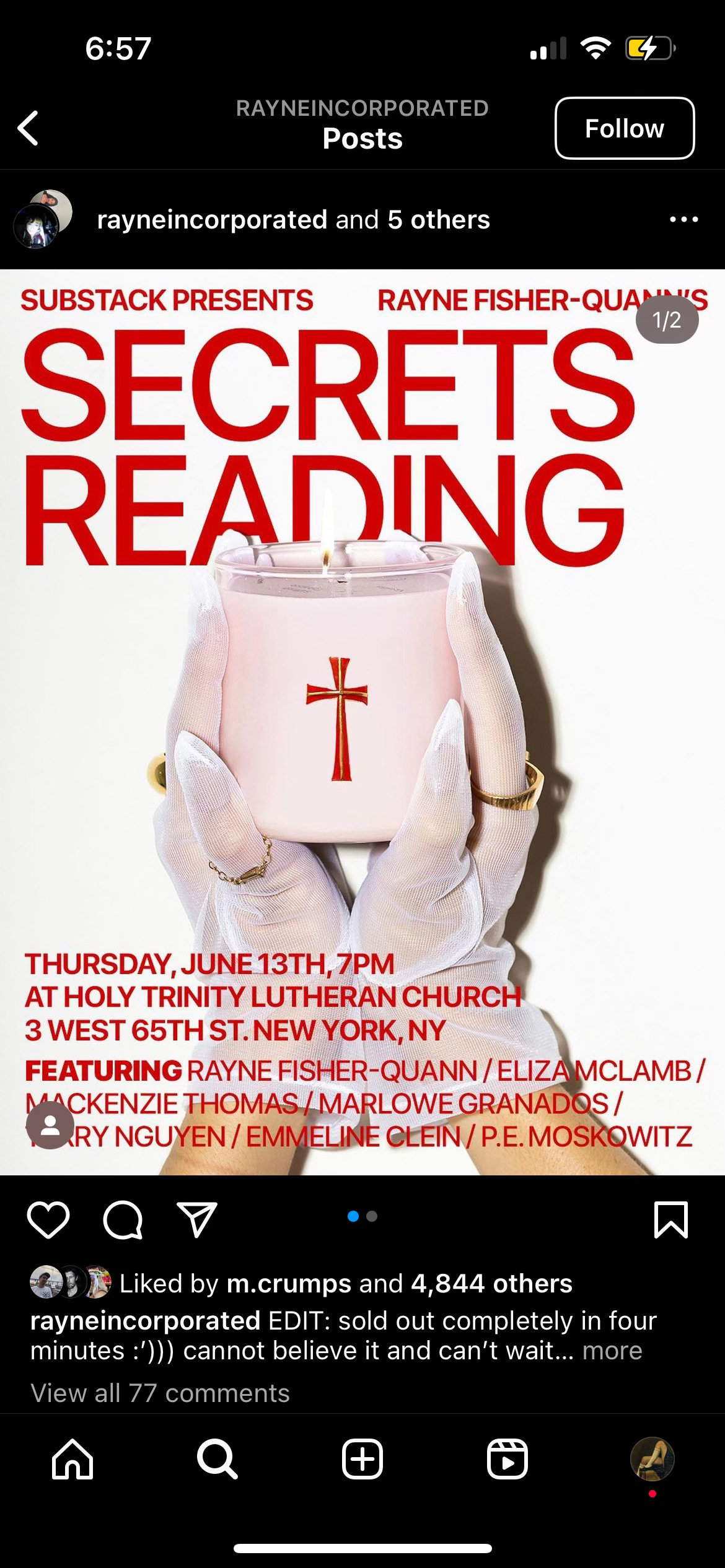

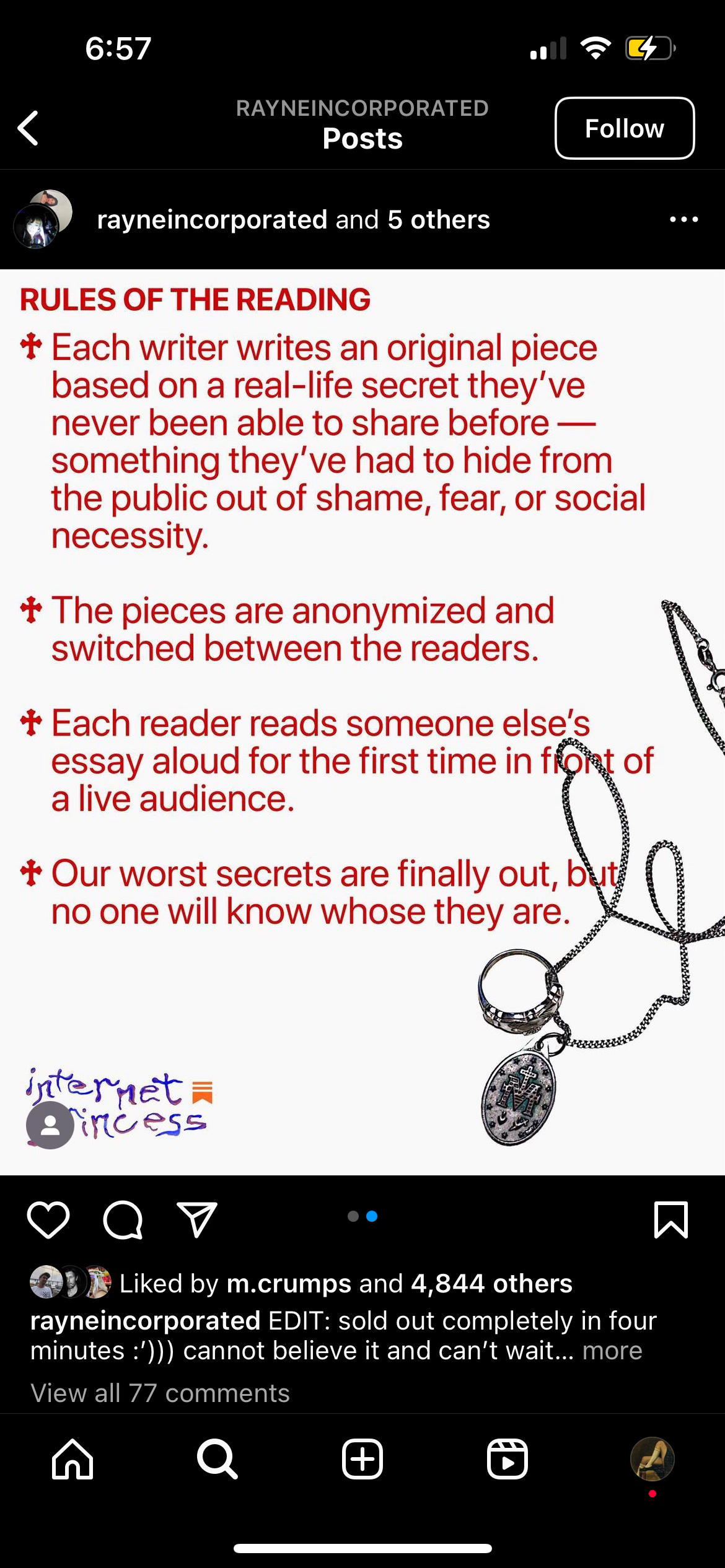

*Please note that on June 13, 2024, a copycat reading series, Secrets, sponsored by Substack, was started by a writer named Rayne Fisher-Quan at a church on W 65th Street. This series is very similar in concept to Confessions, so similar that it either cries plagiarism, or that it reflects Cassidy’s enormous influence. Of course, Fisher-Quan is a “woke” writer with a major publishing book deal, so it all makes sense.*

*As of mid-May 2024, Angel Tramp was no longer cohosting with Cassidy. Instead, a writer/actress named Annabel took over those duties.*

About the Author:

Tejas Desai is an Amazon #1 Bestselling, multiple award-winning author of two dynamic book series: The Brotherhood Chronicle international crime trilogy (The Brotherhood, The Run and Hide, The Dance Towards Death) and The Human Tragedy literary series (Good Americans, the unpublished Bad Americans). He is the founder of The New Wei Literary Arts Movement and runs its associated Salons. He is a graduate of Wesleyan University, attended the University of Oxford, holds two Masters degrees from CUNY-Queens College. While he travels frequently, he works as a Supervising Librarian at one of the busiest public libraries in New York City, where he was born, raised, and of course, still lives.